The Feedback Formula

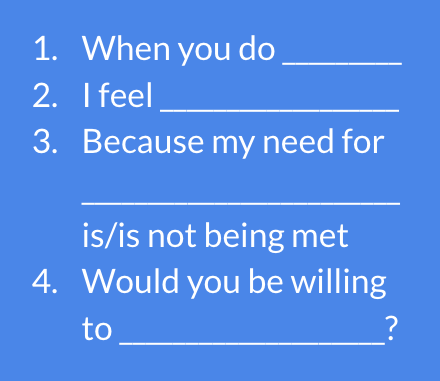

NVCC in a Nutshell

Photo by Michal Matlon on Unsplash

Is there a word in the corporate world that inspires more fear than “feedback”? We’re told it’s a gift, but if that’s true it often feels like a too-small sweater knit for you after you told the knitter you were moving to the tropics, or that time at the white elephant exchange when you were stuck with a failed gag gift (none of the laughs, all of the awkwardness). Yet we want to learn and grow, and we feel more motivated when we’re getting useful coaching that helps us get better. The problem is that most of us aren’t good at giving (or receiving) feedback.

I’ll write about receiving feedback in a future post. For now, here’s a formula from the book Nonviolent Communication that can make you a better feedback-giver. Practicing will also help you get better at receiving feedback because you’ll start to see the places where a clarifying questions can help both you and the person giving you feedback.

The Formula

You can use this formula when you want to give feedback in a context where preserving the relationship is important. For one-off conversations and conversations where the relationship is already too broken to fix, it probably doesn’t make sense to spend your time or the other person’s time on this conversation. But if you genuinely want to help and you aren’t just giving an order (more on that below), try using this formula.

Let’s break down each of the 4 parts.

1) When you do _____

This is where you separate observations from judgments. Observations use neutral, factual language. They are as close as you can come to describing what actually happened. Judgments, in contrast, are your opinion about what happened. If you’re not sure, ask yourself if you’re making any assumptions. For example, saying “you are ____” or “You + [verb ending in ‘ed’] + me.” If so, you’re probably making a judgment.

Judgments put the other person on the defensive and create an issue to debate. For example, consider “you criticized me” versus “you left 12 comments in the Google document”, or “you are lazy” versus “You’ve been late to work 5 times this month.” The more you can stick to what actually happened, the more likely you are to keep the conversation neutral.

One great thing about this is that even if you don’t use any other part of the formula, learning to separate observations from judgments will make you a better teammate.

2) I Feel _______

This one is a little tougher since most of us don’t like to talk about our feelings at work. But it’s worth it because it will take the other person off the defensive. Now, instead of telling them what they “did wrong,” you’re opening up a bit about yourself and enlisting them in helping you.

There are two key pieces to this piece of the formula. First, learn to distinguish feelings from thoughts. Thoughts, like judgments, are more likely to include assumptions, and so they are more likely to be met with counter-arguments. One easy way of telling the difference is that when you are sharing a feeling you won’t need to use the prefix “I feel.” A feeling can almost always be preceded by “I am”, e.g. “I am angry” or “I am happy.” A thought, in contrast, is usually followed by the word “that,” and doesn’t make sense if you remove “that” from the sentence, e.g. “I feel that you should know better.”

Second, distinguish between your own feelings and your interpretation of someone else’s behavior. One way to tell the difference is to ask if the feeling could exist without another person. For example, “I feel unimportant to the people on my team” vs “I feel unhappy.” To help identify you-centric feelings, the CNVC has a great list of examples here.

Again, by focusing on your own feelings you keep the focus on the impact the behavior is having on you, instead of creating an argument. Plus focusing on your feelings keeps the other person from, as they say, getting to live rent-free in your brain.

Even if you don’t get the second part of this quite right, though, and even if you don’t go any further through the formula than this, you can still usually have a more productive conversation by pairing “I feel” language with observations. For example, saying “When you wrote back to me asking for more examples and cc’d the department, I felt attacked. Was that your intention?” Is still likely to lead to a more productive conversation than “You attacked me.”

3) Because my need for _________ is/is not being met.

Needs, like feelings, aren’t usually topics we like to bring up in the workplace. Yet identifying needs is important because it helps the other person see things your way. Someone else’s actions never directly cause your feeling — another person experiencing the same actions could feel a completely different way. The differentiator is you and your needs, filtered through the lens of your own experience. So stating your need helps the other person understand why this topic is important to you.

Stating your needs also makes it much more likely the other person will give you what you need. After all, if you can’t identify what you need, how can you expect someone else to? And even if the person doesn’t want to do what you’re requesting (see below), they can at least understand why you’re requesting it and offer alternatives to meet your need.

The CNVC also has a great list of needs here; some examples that may apply are “acceptance, inclusion, autonomy, community, honesty, order, reassurance, respect and support.” Again, you don’t need to literally say “I need”; saying “I’m wanting ___” or “Because ___ is important to me” will usually also do the trick. The important part is identifying and being upfront about the underlying need.

4) Would you be willing to ______?

Before you provide the feedback, you should be clear, for yourself, as to whether you’re making a request or a demand. If it’s a request, the other person can say no or offer alternatives. If it’s a demand, they have to comply. Something can still be a request even if you really want the other person to do it, as long as you’re genuinely open to hearing their perspective and offering alternatives.

The reality of work is that occasionally you may have to make demands. If so, be clear and explicit about what the demand is as well as what the consequences are if the other person doesn’t comply. For demands, though, think about not using this framework. It’s a lot to ask someone to listen to your feelings and needs only to have you then make a demand of them, essentially saying that their feelings and needs are unimportant.

When making requests, use positive action language to focus the conversation on what the other person can do in the future. Use clear, concrete language to keep the other person from having to guess what you want them to do. For example, instead of “How could you forget to edit the slide?,” try “Would you be willing to edit the slide now?”

Using the Formula

Using the feedback formula is a skill that takes practice. It’ll be awkward at first and you may get it wrong, but the good news is it’s very forgiving. So even if you just start with “when you did X, I felt Y,” or just start with practicing separating observations from judgments, you’ll still find yourself having more productive conversations at work.

If you do end up using this, I’d love to hear from you (you can comment or email me at tltcoaches@gmail.com).